About making love Hemingway said, “It’s always the same but always different.” Poets might say the same about how they write.

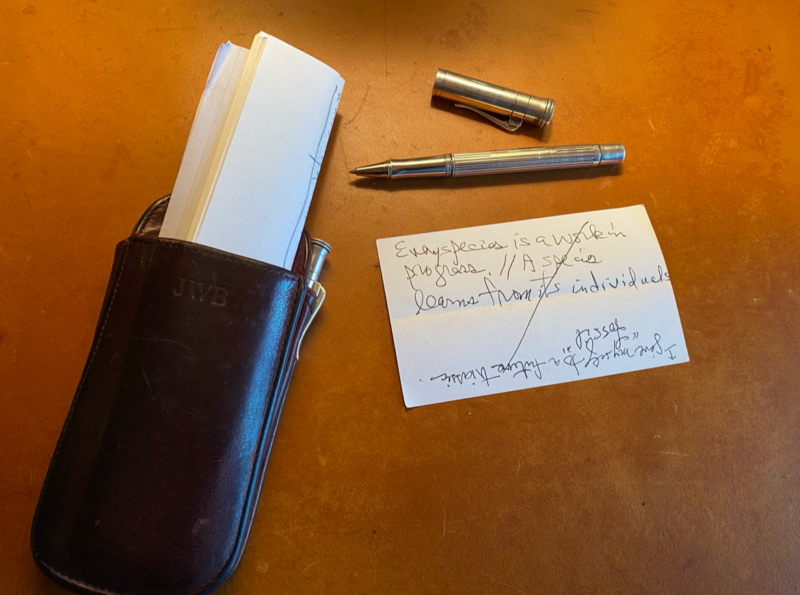

I carry with me 3X5 cards to write down a line when it comes unannounced. Capturing those fugitive lines matters because they don’t last long.

Once, in a movie theater, a line came, and I wrote it down even though I couldn’t see in the dark. When I got home the card was blank: I had written with the wrong end of the pen. Like Mickey Spillane at a crime scene, I shaded the impression with a pencil, and that lost line eventually made it into a poem.

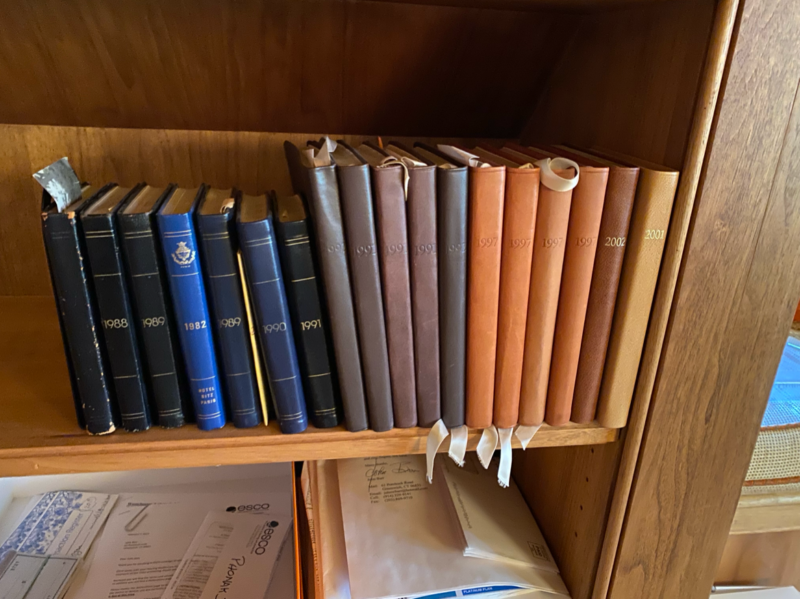

When the cards pile up I copy them into journal books, which, in my case, go back to 1986 (although I was writing, or learning to write, poems 20 years before that). But the journals are more than a repository. In Part 2 of this essay, I’ll explain how.

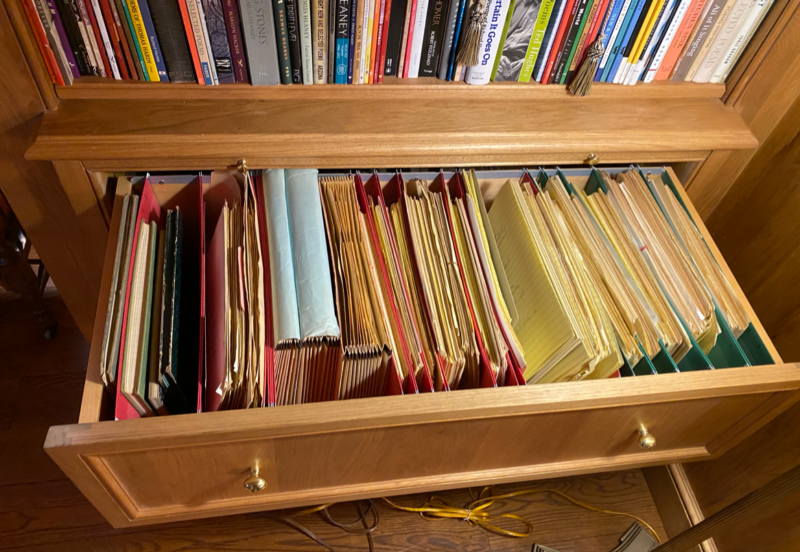

If a line feels like it could turn into a poem I start a file of drafts. In a couple of drawers like this one, the history of each poem comes to rest.

Mss

Since I start things on the margin

— cocktail napkins, cancelled checks,

timetables trying to be reliable —

and since I save it all, I know

there are good words buried and lost

in those fat accordion files, words

that sounded good at the time,

that I promised to get back to,

rhyme trains that never left Grand Central,

monikers that chattered like silverware

at 30,000’, sounds struck

sheer of sense — coin of a realm —

from a currency of air, pronounced

like blessings on an express world,

soul puffs, plain mistakes,

angels, working definitions of.