Emily Dickinson’s example permits all “Nobodies” to believe in their own work in spite of the world’s neglect. And I say, bless her for that.

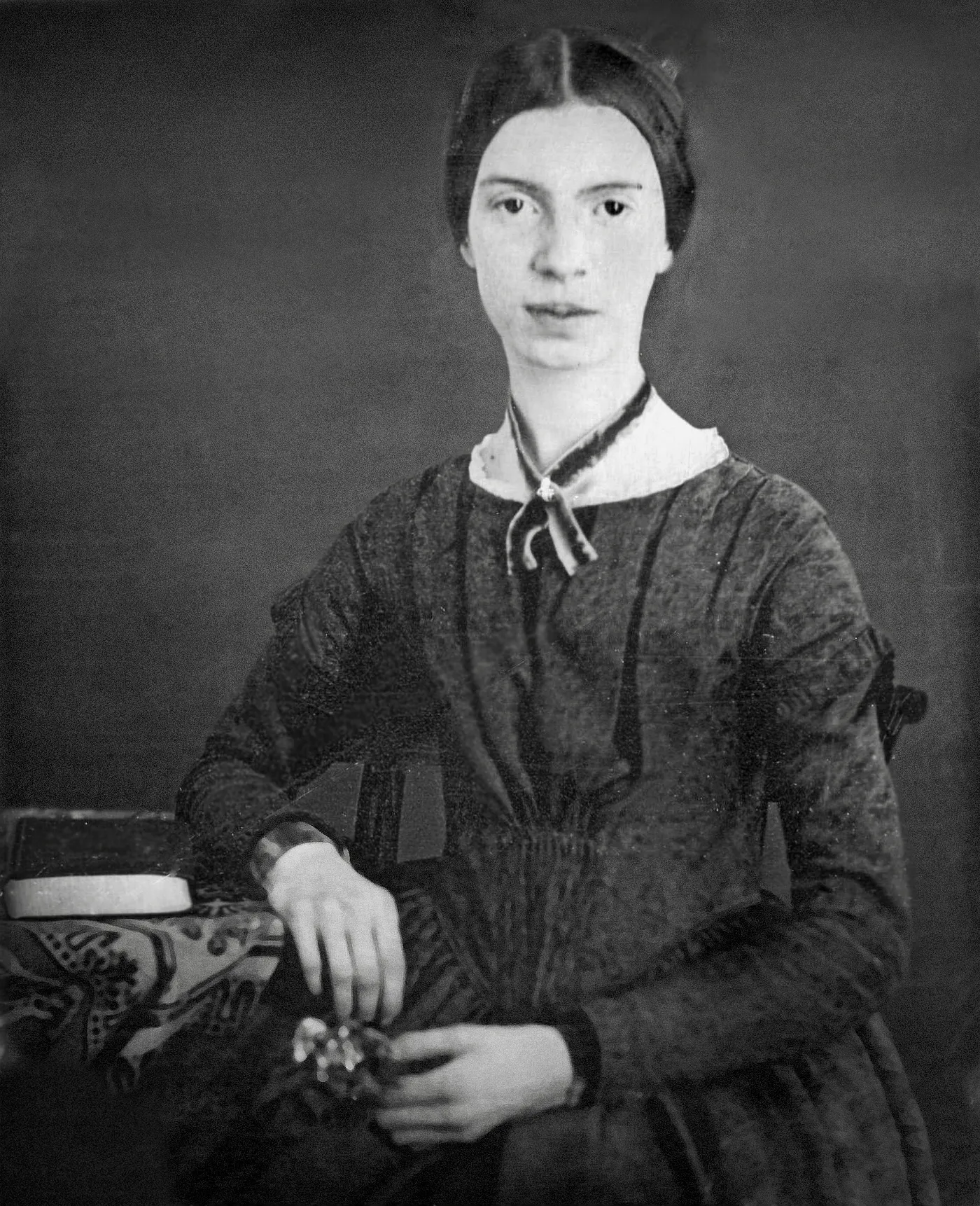

Emily Dickinson’s poems first appeared in book form four years after her death on May 15, 1886. It sold through six printings in six months, and collections of her work have been in print ever since. On a parallel track the biographical and critical attention that has been lavished on Dickinson by scholars, although it came a half century after her popular reception, is a veritable industry today. The list of American poets whose work enjoys both kinds of attention — a broad popular readership as well as serious critical attention — is very short. Robert Frost would be on the list, but Emily Dickinson stands at the head of it.

It is tempting to call Dickinson our first Feminist Poet — except that Anne Bradstreet preceded her by 200 years. I do, however, believe she can be called our first Modernist poet. American poetry, in Dickinson’s 19th century, was essentially English poetry written on American soil. (When Frost wrote “The land was ours before we were the land’s” he could have been talking about American poetry.) But Dickinson ignored the tight forms and English traditions in which Longfellow wrote. In her writing principles and spirit she was a progenitor of Modernism decades before Pound and Eliot. Her fierce independence of mind was Modernist in its impatience with conventional thinking. The brevity of her lyrics — they almost read like shorthand — anticipated what Pound would later call his principle of “concision.” And the passionate and private matters that drove her lyrics preceded the Confessional Poets by a century.

Only a handful of poems were published in her lifetime, and some of those may have been without her knowledge or consent. The worth of her work — nearly 1800 poems by the end — she knew full well. But that knowledge struggled against a painful shyness that became a phobia beyond her control and rendered her unable to promote or even present her poems to editors and to the public. That self-imposed self-effacement makes her the special friend, the patron saint, of poets who write in anonymity or who have an aversion to self-promotion.

I’m Nobody! Who are you?

Are you — Nobody — Too?

Then there’s a pair of us!

Don’t tell. They’d advertise — you know.

How dreary — to be — Somebody

How public — like a Frog —

To tell one’s name — the livelong June —

To an admiring Bog.

Her example permits all “Nobodies” to believe in their own work in spite of the world’s neglect. And I say, bless her for that.

What we have in the work of Emily Dickinson, then, is a large body of lyric poems that was created in isolation, and without the hope of a future readership. Coming to us by the slenderest of chances, her work has been able to establish its relevance to each successive new school of poetry as the art form has continued to evolve in America. I think that will continue as far as eye can see, or poets can write. Her lyrics, simple to the ear but profound upon reflection, are sure of a continuing popular readership. And the absence of a literary “style,” which itself will grow dated, seems to keep the work fresh and open to whatever school of poetry comes next. Emily has done what every poet tries to do and rarely achieves: make something that will last forever in a world where nothing lasts forever.